The proportion of adults with diabetes around the world has risen from 4.7% in 1980 to more than 8.5% today. More than 422m people now suffer from diabetes – so there is an urgent need to better understand the disease and develop new treatments. However, new research from Heidelberg University in Germany suggests that we may have got the causes of type 2 diabetes wrong. But have we? And if so, how might it affect treatment?

People with diabetes need to carefully monitor their blood-sugar levels. This is important, as it helps to reduce the risk of developing complications, such as heart disease and blindness. But even with good control of blood-sugar levels, people with diabetes often go on to develop further complications, including nerve damage and kidney damage. This suggests that effective treatment of diabetes requires more than simply good control of blood-sugar levels.

Type 2 diabetes – often associated with obesity – happens when the pancreas doesn’t release enough of the hormone, insulin, or the body’s cells don’t react to insulin. (Insulin helps the body use glucose for immediate energy needs or store it for future energy needs.) This means that sugar (glucose) stays in the blood and isn’t used as fuel for energy. The cause of these defects remains controversial.

The latest research, published in Cell Metabolism, suggests that a molecule called methylglyoxal (MG) may cause many of the defects associated with type 2 diabetes. But what does it do?

MG is a reactive metabolite (a byproduct of cells) that leads to the formation of other powerful molecules that are readily able to modify protein, fats and DNA in cells. This typically prevents those molecules from working – and this can then result in cells no longer functioning properly. These events are known to lead to the development of diseases such as atherosclerosis, which can trigger strokes and heart attacks.

MG is formed as a result of metabolic pathways – a linked series of chemical reactions occurring in a cell – that are overactive in diabetes and obesity. So it was previously thought that MG production was the result of obesity and diabetes. However, this new research suggests that MG might also contribute to the development of these conditions.

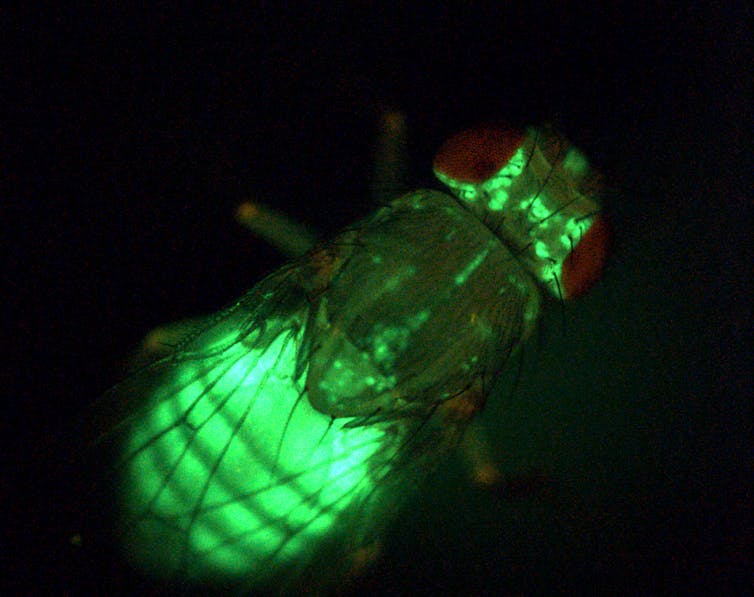

Using genetic engineering, the researchers turned off the enzyme that breaks down MG in flies. MG then accumulated in their bodies and the flies developed insulin resistance. Later they became obese and as time went on their glucose levels subsequently also became disrupted.

These new findings might help explain why, even with good control of blood-sugar levels, diabetic complications still develop. There are important implications from this work, as this suggests that it might be possible to slow down – or even prevent – diabetes complications from developing through a combination of good glucose control along with MG reduction.

What does it mean for diabetes treatment?

While diabetes treatments are often effective at bringing blood-sugar levels down, over time their effectiveness usually decreases. As such there is an urgent need to develop new drugs that work to control diabetes and its complications in different ways.

Most current strategies aim to stop the development of type 2 diabetes by targeting cells and tissues linked to insulin secretion from the pancreas, glucose uptake into cells, or by preventing glucose release from stores in the liver. Together these strategies can help control blood-sugar levels.

The new research, however, suggests that in addition to controlling blood-sugar levels we should also consider additional treatments that work by preventing reactive metabolites, such as MG, from forming. But what would be the best way to achieve this?

Reactive metabolites can lead to extensive damage within cells. There is good news, though, in that there are molecules that can effectively stop these products from forming.

Antioxidants, such as vitamin C and vitamin E, have previously been suggested as possible diabetes treatments. However, studies using this approach have had mixed results. One possible explanation for this is that there are multiple reactive metabolites, not all of which are sensitive to antioxidants.

A new champion may now have emerged, though, in the form of the naturally occurring nutritional supplement called carnosine. This is a molecule that was recently shown to prevent formation of numerous reactive metabolites that are formed from glucose and fatty acids.

[amazon_link asins=’B007DJAFQA,B001MFBQG4,B00IORR9KK,B00K5N2UM8,B00JWYA4HO,B0013OVV4G,B00L7X6QP2,B0026CD0PC,B005FMZT2W’ template=’ProductCarousel’ store=’scottwalkethe-21′ marketplace=’UK’ link_id=’0668ffae-2b5c-11e8-aa1f-8be04a9073c3′]

Clinical trials are ongoing, but initial findings are promising. They suggest that carnosine is able to reduce blood-sugar levels, as well as prevent multiple complications that are associated with diabetes. Even better, as this is classified as a dietary supplement rather than a drug, no prescription is needed in order to take carnosine.

Mark Turner, Associate Professor, Nottingham Trent University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.