Intermittent fasting has become increasingly popular and is now gaining a following among athletes.

The practice consists of going without food for periods of varying lengths. Outside these periods, you can eat any type of food in any quantity you want. There are several types of intermittent fasting, including alternative fasting (every other day), modified fasting (reduced calorie intake on two non-consecutive days per week) and time-limited eating (for example, fasting from 6 p.m. to 10 a.m.).

How does intermittent fasting affect athletic performance? And what are the benefits, practical considerations and risks involved?

Varying effects on athletic performance

During physical activity, the body primarily uses carbohydrate reserves, called glycogen, as its energy source. During fasting, glycogen reserves decrease rapidly. So in order to meet its energy needs, the body increases its use of lipids (fats).

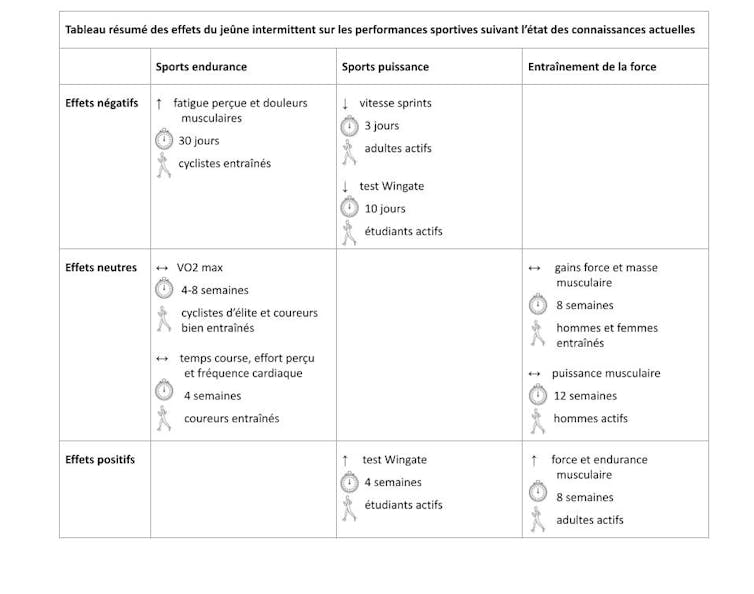

The practice of intermittent fasting has been associated with a decrease in fat mass and maintenance of lean mass in athletes. However, as contradictory results of several studies have shown, these changes do not always improve athletic performance.

Several studies reported that aerobic capacity, measured by a VO2 max test, remained unchanged after intermittent fasting in elite cyclists and runners, as well as in well-trained long-distance and middle-distance runners. In trained runners, there was no effect on running time (10 km), level of perceived exertion or heart rate.

Trained cyclists reported increased fatigue and muscle soreness during Ramadan, but this may be partly due to dehydration, since fluids are also restricted during this period when you cannot consume anything from sunrise to sunset.

Power sports

In the context of fasting, low glycogen (carbohydrate) reserves may limit the execution of repeated, intense efforts. Active adults reported a decreased speed in repeated sprints after fasting 14 hours per day for three consecutive days.

Active students reported decreased power and anaerobic capacity after ten days of intermittent fasting as assessed by the Wingate (stationary bike) test, although the study reported that power increased in the same group after four weeks.

Strength training

Men and women who followed a strength training program had similar gains in muscle mass and strength when practising intermittent fasting compared to a control diet. There was no significant difference in muscle power between active men who did or did not practise intermittent fasting. However, one study reported an increase in strength and muscular endurance in active young adults after eight weeks of strength training combined with intermittent fasting.

So, as we see, the results vary greatly from one study to another and are influenced by several factors, including the type of fasting and its duration, the level of the athletes, the type of sport they practise and so on. In addition, very few studies have been carried out in women. Also, the lack of a control group in most studies means the effect of intermittent fasting cannot be isolated.

So for the moment, it is not possible to draw a conclusion about the effectiveness of intermittent fasting on athletic performance.

Eating before and after training

Athletes who wish to use intermittent fasting should consider several practical issues before starting. Are their training schedules compatible with this dietary approach? For example, does the period during which an athlete is allowed to eat allow them to consume enough food prior to doing physical exercise, or to be able to recover after the training?

And, importantly, what about food quality, given that athletes must consume sufficient protein to recover and maintain their lean body mass and limit negative impacts on their performance?

Questioning the impacts of — and reasons for — fasting

Intermittent fasting may result in an energy deficiency that is too great for athletes with high energy needs to overcome. This could be the case for endurance athletes (running, cycling, cross-country skiing, triathlon, etc.) due to their high volume of training. These athletes may end up suffering from Relative energy deficiency in sport (RED-S), a syndrome that affects hormone secretion, immunity, sleep and protein synthesis, among other things. If the deficit is prolonged, this will have an adverse effect on an athlete’s performance.

It is also important to question the motivation for adopting a dietary practice as strict as intermittent fasting. Some people do it for religious reasons such as Ramadan. Others are motivated by weight control goals and the hope of achieving an “ideal” body according to socio-cultural norms.

A recent study showed a significant association between intermittent fasting in the past 12 months and eating disorder behaviours (overeating, compulsive exercise, vomiting and laxative use). Although this study does not determine whether fasting causes eating disorders, or eating disorders lead to fasting, it does highlight an associated risk in this practice.

Finally, the potential impact of intermittent fasting on social interactions must also be considered. A fasting schedule may limit participation in social activities that involve food. What is the risk of negatively influencing the eating behaviours of other family members, especially children or teenagers who see their parents abstain from eating and skip meals?

Is this a good or bad idea?

With such conflicting scientific data, it is not possible at this time to come to a conclusion about the effects of intermittent fasting on sports performance.

Further studies are needed before this practice can be recommended, especially for seasoned athletes. Furthermore, the potential negative effects on other aspects of health, including eating habits and social interactions, are not negligible.

Bénédicte L. Tremblay, Nutritionniste et stagiaire postdoctorale, Université du Québec à Chicoutimi (UQAC) and Catherine Laprise, Professeur UQAC, Co-titulaire de la Chaire de recherche en santé durable du Québec et Directrice du Centre intersectoriel en santé durable de l’UQAC, Université du Québec à Chicoutimi (UQAC)

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.