When England right-back Kyle Walker takes to the field against Tunisia on June 18 he’ll be making his 54th appearance for club and country this season. That’s a lot of football, more than 3,400 minutes in all. But Walker is not even especially unusual – Leo Messi has played 60 games already, and Croatian defender Duje Caleta-Car has clocked up more than 5,000 minutes this season.

So what happens when, in a World Cup year, already tired players have to extend their season by an additional six to eight weeks and play up to ten more games?

Keeping footballers in perfect shape is particularly tricky as the matches come thick and fast. Research has shown that players are more likely to get injured when games are separated by less than four days. Post-match recovery is therefore crucial – and it’s an issue that colleagues and I recently looked at in our research.

What to eat

These days, players are monitored with Global Positioning Systems (GPS) and data is gathered on total distance run or distance covered at high intensity (sprinting). This means individual players can get their own tailor-made recovery strategy.

For example, players who work at higher intensities (typically the full backs and attacking midfielders) would eat more carbohydrates within the immediate recovery phase. That means more sweet potatoes, rice and buckwheat. The goalkeepers meanwhile would follow a lower-carb diet in order to match their lower energy expenditures.

Just have to say 12 o’clock kick off is no good for players. Trying to force pasta down at 9 in the morning is not nice.

— Wayne Rooney (@WayneRooney) 29 October 2011

However, restoring muscle energy after a match isn’t so simple. Even 48 hours after a game, and after eating lots of carbs, players still don’t manage to increase the glycogen (energy) in their muscles above pre-match levels. This may be attributed to the high “eccentric component” involved in football-specific movements, with resulting muscle damage impairing the restoration of energy.

In particular, two days after eating lots of carbohydrates the fast twitch muscle fibres (responsible for explosive movements such as jumping and sprinting) still had lower glycogen content in comparison to slow twitch muscle fibres (required for more endurance activities).

Practically, this could mean slower recovery times for the more “explosive” players in the team who have a higher composition of these fibres in the muscle. This also has implications for teams that play at a high tempo, and cover more high intensity distance.

Players such as Raheem Sterling and Jamie Vardy who are more explosive and tend to do more sprinting will take slightly longer to replace muscle glycogen in between matches.

Different players, different drinks

Players at the World Cup may have to adapt quickly to playing at different times and in very different conditions. Take England, for instance. They kick off their campaign in Volgograd, where the temperature is likely to be in the high 20℃s or low 30℃s, while their final group game is 1,800km north in Kaliningrad, which has a much cooler Baltic climate.

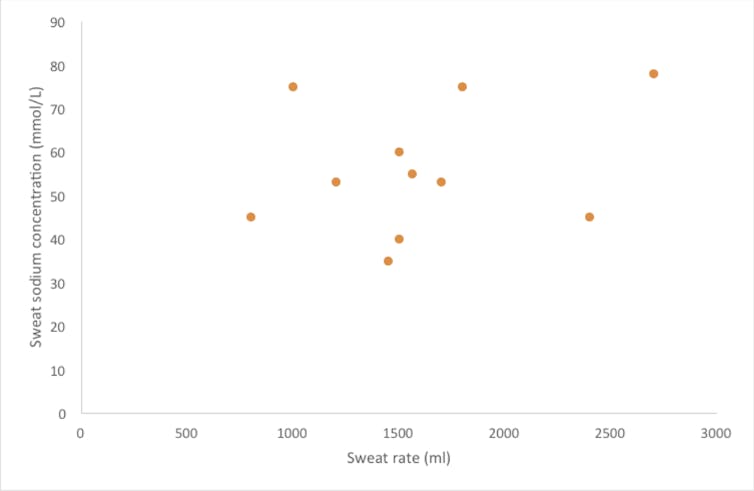

Forward-thinking sport science teams will have measured sweat rates and the sweat sodium losses of their players and should know what to expect for a given amount of running at a given temperature. This can vary hugely from player to player. The graph below shows anonymised data I collected from a Premier League match in which some players sweated at five times the rate of others.

Again, this suggests that players need individualised hydration strategies. For example, one player might lose less sodium but sweat more, whereas another player might have a lower sweat rate but will need more sodium which they can get through bespoke rehydration drinks or by adding additional salt to meals. Players that typically suffer from cramps – always a big danger when world cup matches go to extra time – are likely to have a high sweat rate and a high sodium loss (top right corner of the above graph).

Managers are unlikely to rotate their squads too much because of the importance of every match during the World Cup, so adequate recovery nutrition for key players will be of paramount importance. These strategies are likely to be individualised and driven by detailed physiological data.

An additional challenge that teams will have to contend with is sleep in between games, especially after matches that kick off in the evening. Sleep deprivation will become an issue as a result of late games, so it will be crucial to time the recovery nutrition to optimise a good night’s sleep.

More evidence-based articles about football:

- How AI could help football managers spot weak links in their teams

- Does spending big in the football transfer window get results? Two experts crunch the data

- Why football teams who sing their national anthem with passion are more likely to win

Mayur Ranchordas, Senior Lecturer and Sport Nutrition Consultant, Sheffield Hallam University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

![]()