A newer concept of health known as “allostasis,” which means “stability through change” has immerged.

It argues that rather than simply striving to preserve a steady state of internal balance, the human body and brain are designed to anticipate and make preparatory adjustments based on experience

In ancient Greece, medical minds believed that the function of the human brain and body was dependent on the proper ratio of four internal fluids which were known as the “humors.” Too much or too little of any one of the humors was thought to cause pain, dysfunction, and behavioral or emotional intemperance.

This mixologist’s notion of human physiology continued to dominate medical theory until the 19th century, when doctors finally recognised that “humorism” was mostly bunk. But they couldn’t quite shake off the belief that a sick body is somehow a body out of balance.

The next big idea that emerged — one that became the dominant explanatory framework for physiological regulationfrom the late 1800s all the way up to the present — is the concept of “homeostasis.”

Homeostasis holds that the human body has certain baseline states or “set points” that it strives to maintain.

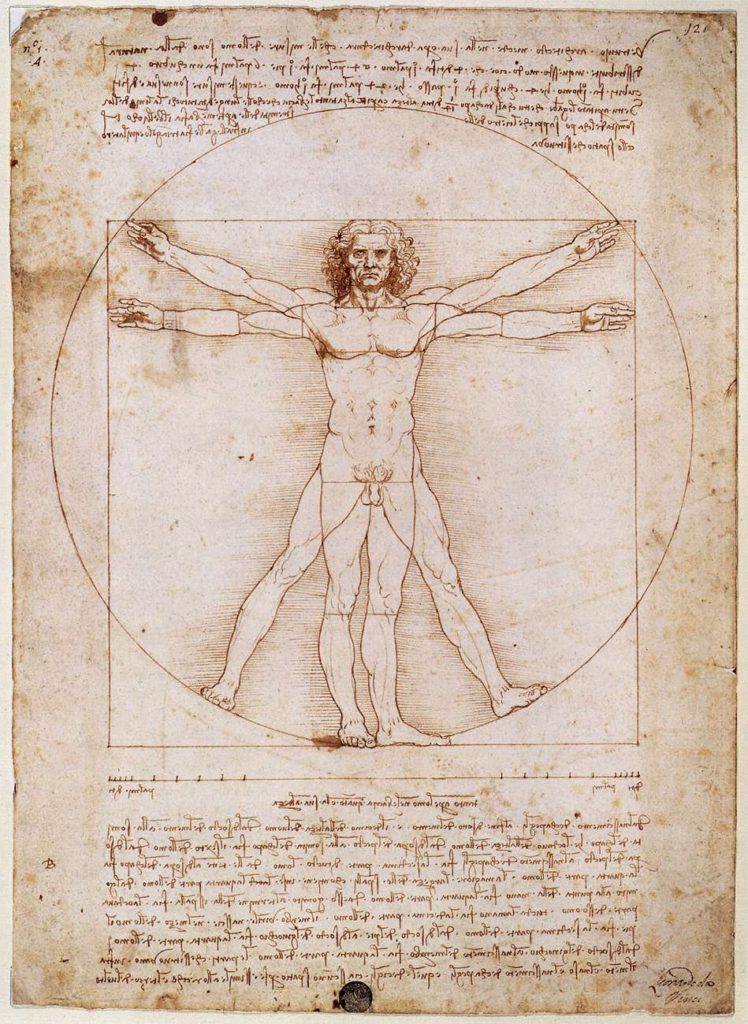

Constancy is the goal, and disease and disorder are the result of deviations from these set points or the body’s unsuccessful attempts to get back to them. Like Leonardo da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man, homeostasis holds that a healthy body and mind are in all ways proportional.

Type-1 diabetes is an example of homeostatic principles at work: An insulin insufficiency causes dangerous disruptions in the blood’s levels of glucose; introducing insulin via injection helps restore balance.

But some experts have challenged the idea that the ultimate goal of the body’s inner workings is to maintain some predetermined set point or state of balance. Homeostasis is all about staying the same, but most physiological systems are about change and adapting to it.

A newer concept of health known as “allostasis,” which means “stability through change” has immerged.

It argues that rather than simply striving to preserve a steady state of internal balance, the human body and brain are designed to anticipate and make preparatory adjustments based on experience.

For example, levels of digestive enzymes and energy-transporting hormones rise before a person eats a meal, and the specifics of these shifts depend in part on that person’s typical diet, eating schedule, and other past behaviours. If that person normally eats an unhealthy, sugar-rich diet, these pre-meal enzyme and hormone shifts — including ones that can contribute to poor energy metabolism and type-2 diabetes — will happen even if the person ends up dining on healthier food.

What the homeostasis model may regard as disorder or dysfunction, allostasis views as a logical response to external events or stimuli — even if that response has some unwelcome drawbacks. “Allostasis takes into account the environment and social contexts and how we adapt to them.

For too long, homeostatic theory has dominated medical science and its approach to research and treatment. Allostasis, by shifting the medical community’s notions of how the brain and body work, could inform more productive scholarship and better maybe especially when it comes to mental health conditions like anxiety and depression.

We need a concept like allostasis that takes into account how we manage to adjust, or don’t manage to adjust, to things in our life.

Allostasis and mental health

Anxiety disorders, depression, and other mental health challenges are often described as the result of chemical “imbalances” in the brain. This homeostasis-influenced view has been around for decades, and it serves as the foundation for contemporary pharmacotherapy. By correcting these supposed imbalances — for example, by increasing levels of the neurotransmitter serotonin — these drugs are intended to improve mood, cognition, or behavior.

But some proponents of allostasis hold a different view. While mental health disorders are frequently associated with elevated or reduced levels of certain neurotransmitters, they say that there’s little evidence that these disorders are caused by neurotransmitter imbalances.

Drugs amount to a blind tweaking of circuits that are not even identified, let alone understood

Peter Sterling, PhD, a professor of neuroscience at the University of Pennsylvania and author of What Is Health? Allostasis and the Evolution of Human Design.

While this kind of tweaking may in some cases help relieve a person’s symptoms, it doesn’t address the underlying causes of those symptoms. Adjusting the brain’s levels of neurochemicals can also interfere with other aspects of mood or cognition, and in some cases can induce bouts of paranoia, anger, or other negative side effects.

“We need a concept like allostasis that takes into account how we manage to adjust, or don’t manage to adjust, to things in our life.”

Sterling, along with the late UPenn biologist Joseph Eyer, coined the phrase “allostasis” and has been developing and refining its model for more than 30 years. He says that the big idea — the thing that really differentiates allostasis from homeostasis — is the recognition that the brain and body are constantly trying to predict and adapt through adjustments to a person’s physiology and behavior.

The most efficient way to run the body is for the brain to figure out ahead of time what will be needed

Peter Sterling, PhD, a professor of neuroscience at the University of Pennsylvania and author of What Is Health? Allostasis and the Evolution of Human Design.

Allostasis concepts help explain why a person whose life is filled with stress may experience worry and its physical manifestations — such as elevated blood pressure, rapid heart rate, and GI discomfort — even during those times when no threat or source of stress is present. Rather than returning to a set point — which is the response that the homeostasis model predicts — the brain has adapted.

In a 2014 paper in JAMA Psychiatry, Sterling explains how this allostatic understanding of the brain and body may inform mental health treatment. If practiced in the right contexts, mindfulness meditation, cognitive behavioral therapy, and other non-drug programs designed to encourage constructive thoughts, attitudes, and behaviors could engage the brain’s adaptation mechanisms in therapeutic ways.

By changing the brain’s experience of life, people can remodel their own neural circuitry in ways that reduce the burden of mental health challenges

A broad conceptual shake-up

Plenty of experts agree that some new ways of thinking and talking about health are needed. Especially when it comes to mental health, a number of doctors have argued that the terms and theoretical frameworks we apply to some of these conditions need refurbishment.

Peter Kinderman, PhD, a professor of clinical psychology at the University of Liverpool in the U.K., says that the current language around mental health pathologises what are in a lot of instances predictable and logical responses to distressing life events, and that it might be better to refer to certain mental health conditions as experiences, rather than disorders.

For example, depression and anxiety symptoms have increased in the U.S. during the coronavirus pandemic. SARS-CoV-2 poses a very real and deadly threat to oneself and one’s loved ones, and it has also contributed to economic, political, and social turmoil. Reacting to all this with feelings of sadness or anxiousness is not “a dysfunction in the biology of the brain,” Kinderman says. “There’s nothing pathological about that response.” Using more appropriate language to describe these experiences could in many cases help people move on from — rather than just manage — what they’re dealing with, he adds.

These sorts of conceptual health debates aren’t going away anytime soon, and they’re of a piece with broader discussions about contemporary life and the way it may be driving historically high rates of metabolic disease and existential torment.

“Homeostasis doesn’t explain why half of the population is obese or diabetic, or why we have such high rates of so-called ‘deaths of despair,’” Sterling says. “I think we’re overdriving the body and demanding too much of these mechanisms that aren’t really broken, they’re just mistreated.”

Embracing an allostasis model of human functioning, he says, may help us better address these growing problems.