Do you know what the problem with science is? As we would say in Australia, “It’s a bit average”.

Us Aussies are known for our dry understatements. In this case, it usually means it is pretty bad. Just like its direct opposite, “not bad”, mean pretty good!

But, in the case of scientific studies, most notably random-controlled trials, the gold standard of interventionist trials, the problem is that the results are ‘average’. That is, what happened on average to the trial groups.

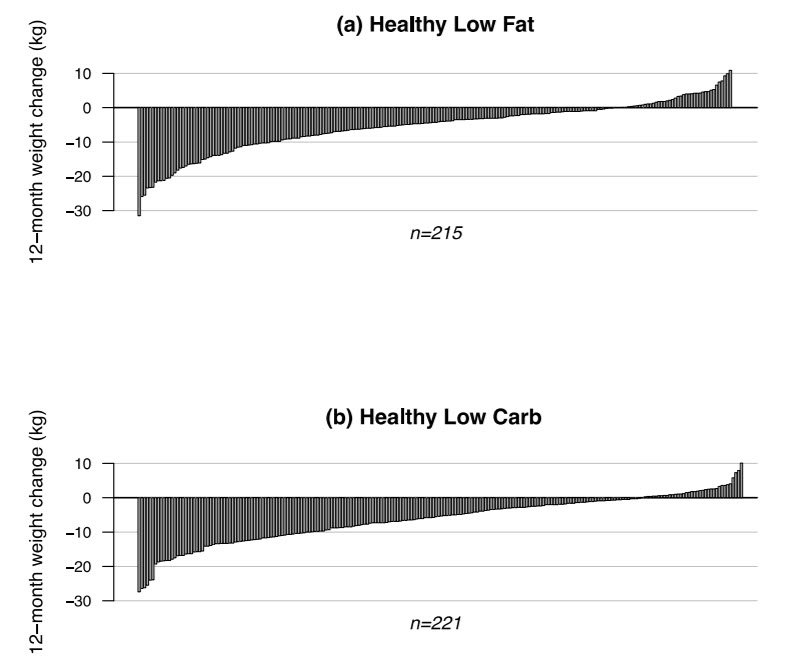

Take for example, a large low carb versus low fat nutrition study that lasted a year, with 600 people, which is a pretty unusually high number of trial subjects. The weight loss difference was virtually identical in the two groups after a year. But the most stunning thing was how variable the responses were to the two diets. In both diet groups, somebody lost 60 pounds and, in both diet groups, somebody gained 20 pounds, in a weight loss study. How would you feel if you signed up for a weight loss study and gained 20 pounds!

There were some people who were put on low carb and put on weight, and there were some people who put on low fat and put on weight, and the reverse.

What was really interesting is they graphed for every one of the 600 people, 300 on each diet, what was the result for each person.

It was an absolute continuum. Somebody lost 60 pounds. Somebody lost 55 pounds. Somebody lost 40 pounds. All the way to the other end of gaining 20 pounds.

What’s the answer?

We need to find more areas of personalisation.

In fact, that is why this study was actually done. The hypothesis was that there might be a predisposition that people who are genetically predisposed because of some genetic mutation one way, or the group that was the most insulin resistant versus insulin sensitive would help explain some of these result. Other research has disproved the genetic theory, because even identical twins respond differently to the same diet.

We need to move beyond looking at the average, looking at the mean of the population.

This is what dietary guidelines are based on, the average response to food. The discussed study clearly shows that if you look at the average, they’re exactly the same. But if you look at how each individual response, it’s hugely different.

We see this in other research. We see a 20 fold difference from one person to another in their blood sugar response to exactly the same meal. For example, if we feed people exactly the same breakfast, control as many of the other conditions that we know impact your blood sugar response – fasted overnight, done no exercise – and we still find a 20 fold difference, which is huge to giving them exactly the same breakfast.

In the meantime, if they chose a whole food, highly plant based diet, some are likely to do better on higher fat and lower carbs, some just the opposite. That’s not bizarre. That’s almost, that should be expected.

That is why, a test-based, individualistic approach must be adapted

You should still eat well today and we have some basic guidelines. But, make sure you get tested and conduct your scientific studies of n=1.