Welcome to part three of The science behind weight loss, a Conversation series in which we separate the myths about dieting from the realities of exercise and nutrition. Here, Professor Susan Paxton, from La Trobe University’s School of Psychological Science, takes a look at body image pressures and disordered eating:

You just need to catch a glimpse of a magazine news stand or a fashion billboard to get a sense of why so many Australians are dissatisfied with their body shape and weight.

Our society vigorously supports an unrealistically thin body ideal for women and a lean, athletic body ideal for men, and ascribes qualities of moral virtue to the few who achieve these ideals.

On the other hand, people with larger body sizes are stigmatised and assumed to be morally deficient.

Consequently, a very large proportion of the community lives in a state of anxiety and self-criticism related to their body size and shape.

In an attempt to improve their body size or shape, many people turn to unhealthy fad diets.

An Australian study by Hay and colleagues (2008) found that one in five 15-24 year olds reported strict dieting or fasting. Almost 30% said they went on food binges and 14% purged what they ate to control their weight.

But it’s not just a problem for young people. Body dissatisfaction continues into adult life and remains high, at least into midlife. Of the 45-54-year-old respondents:

- 21% reported strict dieting or fasting;

- 17% reported binge eating; and

- 29% reported purging for weight control (more than double the rate of the younger cohort).

Increasing body satisfaction

Body dissatisfaction and disordered eating are not only associated with distress, they can also contribute to low self-esteem, depressive symptoms and clinical eating disorders. So prevention and treatment need to be taken seriously.

My colleagues and I have evaluated a number of interventions and group therapy programs that aim to reduce body dissatisfaction and disordered eating for adolescent girls, young adult women and women in midlife.

Our goal has been to reduce negative attitudes and behaviours, such as the endorsement of society’s unrealistic ideals of appearance and the tendency to compare one’s own body with the bodies of others.

The group therapy programs we investigated helped participants learn new ways to manage environmental pressures that increase the risk of body image and eating problems, such as:

- appearance-focused peer environments, where appearance and weight loss dominate conversations;

- verbal abuse, based on appearance;

- criticism of appearance on social networking sites; and

- perceived pressure from media or family to conform to the ideal.

Our school-based intervention for grade seven girls, Happy Being Me, is one such program. We help girls build a peer environment where they can feel positive about their appearance.

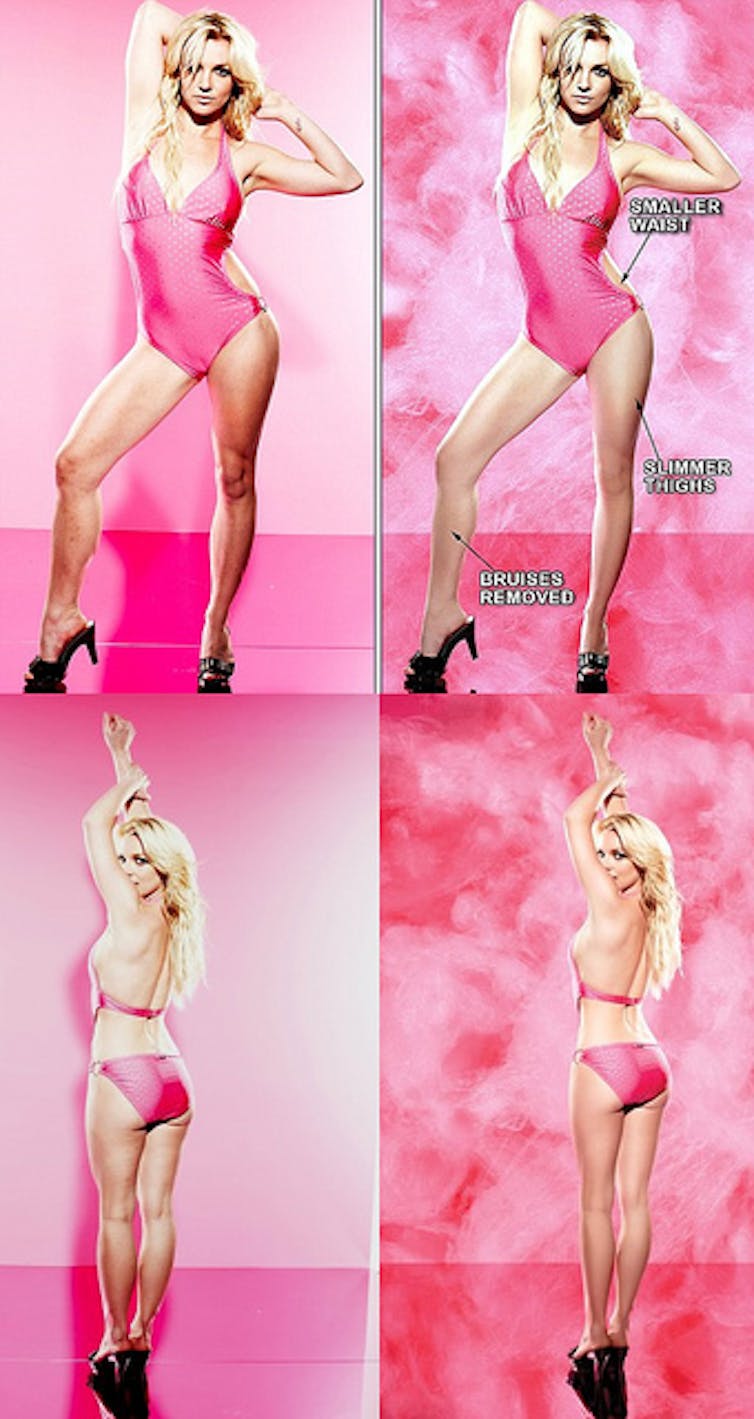

The girls learn about the negative impact of appearance and diet-related conversations. They also gain some insights about the way images of celebrities and models are retouched and, when published, bear little resemblance to reality.

Some teenage girls, however, have more severe body image and eating problems that require more intensive therapy.

We evaluated one such program for teenage girls, which ran over six sessions. My Body, My Life was delivered by a therapist over the internet using chat-room technology, so participants didn’t have to travel.

The evaluation showed the program resulted in important improvements in the participants’ body image and eating behaviours.

Similar group therapy programs have also achieved results for young adult women (Set Your Body Free) and women in midlife (Set Your Body Free – Midlife). This caters to the specific needs of women in midlife, who juggle work with family life and may not have the time or energy to look after their own needs.

We’re making some progress in countering the influence of unrealistic body images in the mainstream media. But giving individuals of all ages the skills to cope with constant unrealistic pressures is just one battle.

We also need to bring about social change which ultimately removes or reduces these pressures.

This is the third part of our series The science behind weight loss. To read the other instalments, follow the links below:

Part One: Diets and weight loss: separating facts from fiction

Part Two: Want to set up a weight loss scam? Here’s how…

Part Four: Food v exercise: What makes the biggest difference in weight loss?

Part Five: An online tool to help achieve your weight-loss goal (no, it’s not a fad diet)

Part Six: Ignore the hype, real women don’t ‘bounce back’ to their pre-pregnant shape

Part Seven: Quick and easy, or painful and risky? The truth about liposuction

Part Eight: Weight loss and the brain: why it’s difficult to control our expanding waist lines

Part Nine: Are diet pills the silver bullet for obesity?

Susan J Paxton, Professor of Psychological Science, La Trobe University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

![]()