Alcohol misuse is a major public health concern, and there is considerable evidence that heavy drinking is associated with a range of negative health outcomes, including cancer. However, the link between light to moderate drinking and health is more complex.

Previous studies have consistently found that light to moderate drinkers live longer than lifetime teetotallers. The evidence from cancer research gives a different impression: even light to moderate alcohol consumption is linked with an increased risk of cancer. These differences have led to confusing public health messages about the health impacts of light to moderate alcohol consumption and what counts as drinking in moderation.

To help give a clearer message, we decided to assess both cancer and mortality outcomes together, using the same methods and same population, to see what the overall link between alcohol and these major outcomes are.

For our study, published in PLOS Medicine, we used data from nearly 100,000 people involved in the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, Ovarian Cancer Screening Trial who had completed a dietary questionnaire with questions on their alcohol intake at various stages of their life. We averaged their alcohol intakes over their adult lifetime until the start of our study.

What we found

Previous studies have tended to separate former drinkers from current drinkers and classed them as non-drinkers. This separation can underestimate the negative health effects of drinking, as former drinkers may have stopped drinking due to health scares related to their drinking habits. Instead, we looked at the average lifetime alcohol intakes, which avoids separating former drinkers from current drinkers.

We then linked this data to data that showed which of these people were diagnosed with cancer, or died over an average of nine years after completing the questionnaire. This allowed us to assess whether the combined risk of developing cancer or dying within these years differed between people with various levels of alcohol intake.

We attempted to account for as many other differences between these groups as possible, such as smoking and diet, so that we could be more sure that any differences in risk between drinkers and never drinkers were due to differences in their alcohol intake.

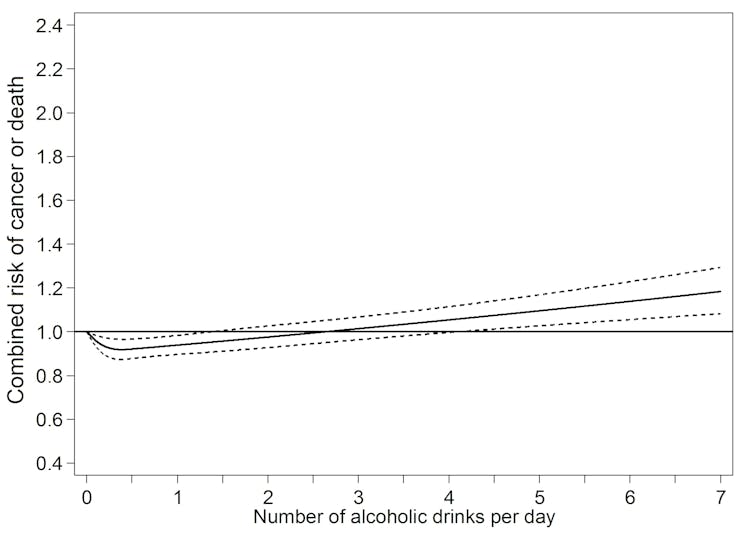

The results indicated that a J-shaped relationship (see graph below) between alcohol and combined risk of cancer or death was apparent, with the lowest risk apparent in people drinking less than seven alcoholic drinks per week (less than one drink per day) – where one drink equates to about the units found in a medium strength bottle of beer – compared to never drinkers or heavier drinkers. Heavier drinkers (who drank more than three drinks per day) were at a 20% higher risk of getting cancer or dying prematurely than light drinkers.

Drinking alcohol is a personal choice and it is not our aim to tell people whether they can or can’t drink. The aim of this study is to provide robust evidence so that people can make informed, healthy decisions about their alcohol intake.

We urge caution in interpreting the results comparing light drinkers to lifetime teetotallers, though, as the reasons for the reduced risk of cancer or early death in light drinkers are still being debated by scientists.

It has been suggested that light drinking may have beneficial effects on heart health, though this has not yet been proven. Light drinkers may also be at a lower risk of premature death as they tend to be wealthier, so may have better access to healthcare and may follow other healthier lifestyle behaviours, such as being more physically active. Until the debate is settled, it would be unwise to suggest that non-drinkers should begin drinking as a way to benefit their health.

Guidelines may need updating

There are large differences between countries in alcohol-related guidelines about what is considered to be drinking in moderation. The UK recently lowered its guidelines to suggest that both men and women do not drink more than six alcoholic drinks per week. The US guidelines are higher for men and recommend less than 14 drinks per week for men and less than seven drinks per week for women.

We hope that our results will help to inform future public health guidelines around the world regarding alcohol consumption. It’s time for consistent messages about what counts as drinking in moderation. Our findings suggest that drinking in moderation might be less than seven drinks per week.

Andrew Kunzmann, Postdoctoral Research Fellow, Queen’s University Belfast

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

![]()